image 'Star Blossom' from Pixabay

article by Root Cutbertson 2023 ![]()

part of a series on Regenerative Design Principles.

“There are no separate systems. The world is a continuum.” – Donella Meadows

“Everything, the whole universe, everything in it, is one unbroken wholeness.” – Dave Hora

A fundamental organizing principle of living systems is wholeness.

Caution! Hazard: if you were raised in a westernized society, you may have been conditioned by a worldview based on separation to think about parts more than wholeness. This has happened a lot. Thinking about wholeness can feel like stretching your brain in strange new directions. You may feel some discomfort or resistance. Don't worry too much if you struggle with this. As an author, i often struggle with this. It doesn't help that the modern English language tends to reinforce a worldview of separation. English is based more on nouns than on verbs, emphasizing objects more than processes. (As designers, we may benefit from co-creating new language as we go!) The words here represent my best attempt as an author at the time of writing. i am painfully aware of their limitations. Please forgive me if you find them imperfect or unhelpful.

For infants and young children, perceiving wholeness can be simple and straightforward. Many infants begin their life with a sense of undifferentiated wholeness, and develop more perception of separation as they grow. Young children, while their identity and individuality is still fluid and not-yet-fully-formed, can often access their empathy, imagination, and 'magical thinking.' In westernized societies, a common pattern is for children to 'outgrow' these perceptions, along with their perception of wholeness. For more mature adults, perceiving wholeness can feel like trying to remember ways they perceived the world during childhood. It often involves a shift in perspective away from what has become habitual thinking.

image by Sergio Cerrato/Pixabay

Systems Thinking

When you begin shifting your perspective to perceive wholeness, you begin to engage in systems thinking, which underlies how you understand and interact with living systems. Fritjof Capra describes systems thinking as emphasizing wholeness instead of parts. It is “a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things; for seeing patterns of change rather than static 'snapshots.'”

At first, some patterns and interrelationships may be easier to perceive. For example: a child who enjoys watching (and catching!) tadpoles, may become curious about their amphibian metamorphosis into frogs; and then about the predators who eat them; and then about the wetlands where they live; and then about how their life cycle interacts with their environment (what kinds of bugs they eat, what happens to their poop, where they lay their eggs, how they survive the winter, what happens when they die). A child often relies on adults to tell them stories that reveal such patterns and interrelationships. And if the child pays enough attention, they can confirm the patterns in these stories for themselves, or discover new patterns. As they grow older, the child may find similar patterns and relationships throughout the living world (What else metamorphoses? Who else has a life cycle?) Experiences like this can reinforce systems thinking.

No True Separation

On both the micro and macro levels, there is no true separation. When two 'solid' objects 'touch', it is only the electromagnetic fields of their molecules interacting that makes them appear to remain separate. The living systems of our planet are contained by a layered blanket of air: the upper ionosphere gradually feathering into what we call 'outer space;' the lower atmosphere serving to contain the wholeness we call the biosphere or the ecosphere. From this perspective, the many environments of our planet are not truly separate: they are one wholeness.

As designers, perceiving wholeness, in any situation, in any context, (in every situation, in every context) can help us consider whether, when, and how we can best intervene in a living system. When designing it is beneficial to remember that we are also nested within (and in relationship with) the world; that the environment immediately around us is nested within a larger ecosphere; that the wholeness in which we are embedded means nothing is ever truly separate (see 1-2 Nestedness).

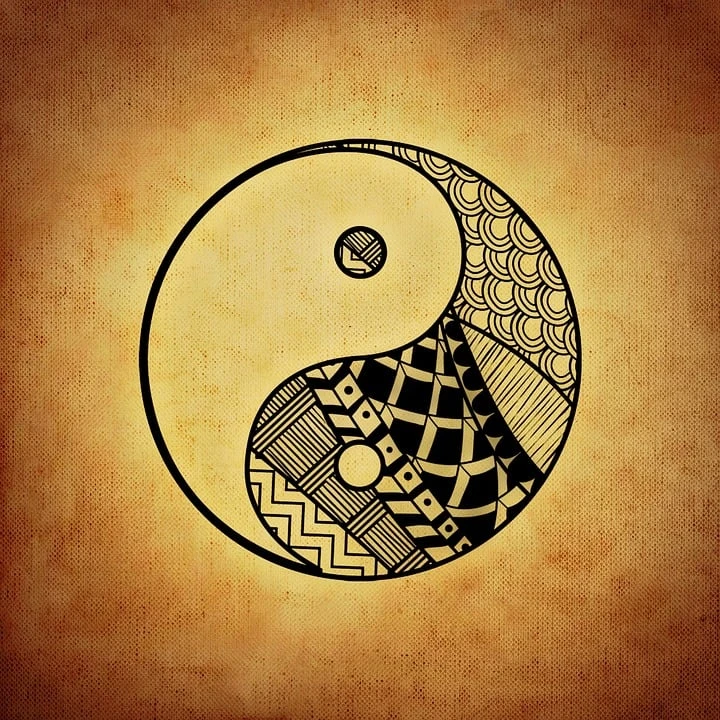

And, while separation may not truly exist at these fundamental levels, human neurobiology evolved to perceive separations. Much of daily human life involves discerning distinctions, gradations, patterns, contrasts, polarities. Our human knack for perceiving separation can be quite helpful at times. It has allowed us to notice aspects of the natural world that we have learned to exploit for our own benefit and survival. It allows us to separate and categorize information so as to more easily convey and transmit ideas to others (much as i am doing now as an author).

Instead of an 'either-or' polarity, a 'both-and' approach may be beneficial. We humans have the ability to perceive both wholeness and separation. We can emphasize one or the other depending on the context or situation.

image by Alexa/Pixabay

Boundaries and Containment

“Where to draw a boundary around a system is arbitrary.” – Donella Meadows

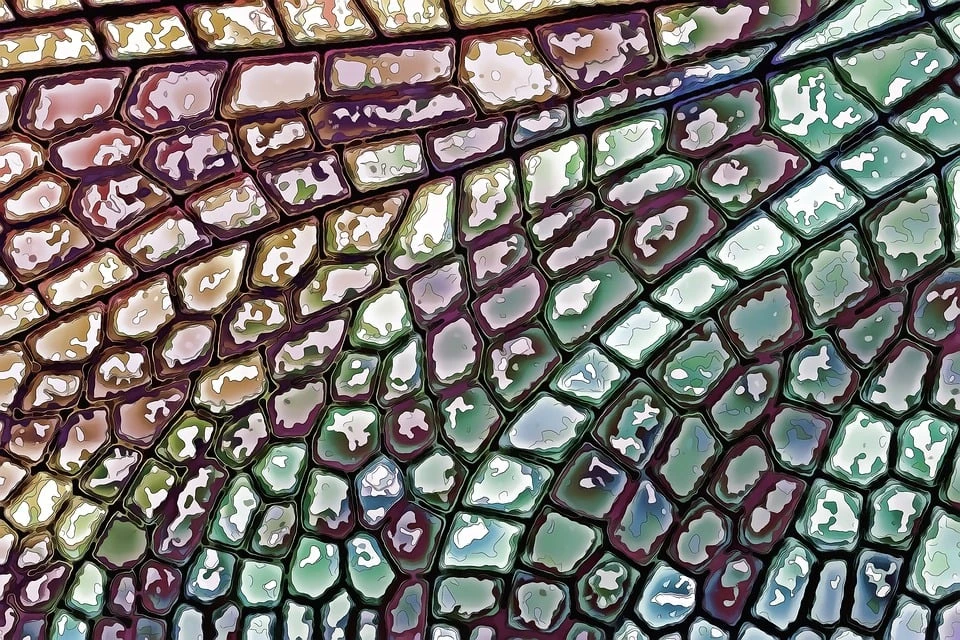

Many people raised in a westernized society are conditioned to identify boundaries: the places where one thing is separated from another thing. This is often accompanied by a worldview that emphasizes the separateness of things. Systems thinker Donella Meadows suggests widening this worldview. When you perceive wholeness, when nothing is truly separate, boundaries become a construction of convenience – a short-hand way to describe distinctions and differences. When you perceive wholeness, you know that the separation of boundaries is not the ultimate reality; and, simultaneously, boundaries may be helpful for a time, to help you more accurately describe your perceptions to others.

The shift in perspective that accompanies systems thinking reimagines boundaries: instead of impregnable barriers that enforce separation, they are more like permeable membranes (see 3-4 Membrane/Threshold). They are places of connection where nested components interact (see 1-2 Nestedness). They are open to exchanging with and being influenced by neighboring systems (see 1-7 Networks, see 7-8 Allow Flow). They provide an edge or margin where experimentation, diversity, mixing, adaptation, and evolution are encouraged and make sense. A boundary might even be a temporary frame that allows an exploration of a certain pattern or set of relationships. It might reflect an agreement that affects a wider system, or even the entire whole: a specialization, a localization, or a concentration that provides wider benefits.

For example: the human body is composed of cells organized into several systems, which all interact to provide benefit for the whole. Every cell's DNA carries a map of the entire whole: it is possible to clone an entire human, with all its systems, from the DNA within a single cell. Every cell, however, 'agrees' to only express a portion of the entire map. Clusters of similarly expressed cells form concentrations and specializations within the body, sometimes even forming a membrane around the cluster. These clusters form organs, bones, nerves, skin, tissues. Lung cells, for instance, are clearly distinct from other types of cells. They form a membrane around the organs called lungs. Across this membrane, lung cells regularly interact with other systems: circulatory system, nervous system, endocrine system, digestive system, muscular system. They specialize in obtaining and providing key benefits for the entire whole.

For example: an arbitrary boundary might help a group explore within a temporary frame, to better understand patterns and relationships. A team-building exercise called 'Cross the Line' invites separating into a number of temporary groupings, based on obvious or not-so-obvious characteristics or experiences. Such groupings call attention to patterns in how group members typically interact; and how awareness of those patterns might shift those interactions. Raising awareness around shared characteristics can help reduce a sense of separation and increase a sense of connection.

Everyone 'cross the line' who:

has brown hair

has one or more sibling

speaks more than one language

has ever eaten rice

has been affected by a disability, your own or someone you know

has been affected by the death of a family member

has been discriminated against or the target of an unfair stereotype

has been bullied

has stood by and felt helpless while witnessing someone being bullied

has been a bully

has felt alone, unwelcome, or afraid

has wished to change something about their body

has questioned their gender identity

has received help from a stranger

has stood up for something they believe in

It may be helpful to remember that frames and boundaries can be temporary. Living systems can adjust or re-arrange their own boundaries, depending on the situation – so they might last for a longer or a shorter time. A basic Buddhist belief suggests that everything can be perceived as temporary, especially from a long-term perspective. In time, separate forms arise and pass away, while an underlying wholeness remains.

Carol Sanford describes living systems as including “structures of support and containment.” Containment is an important aspect, because it defines the limits of a system. A living system's regulation only affects whatever is contained within its boundaries (see 3-3 Feedback, see 3-4 Membranes, see 3-6 Contain Reactions). This relates to the principle of Nestedness, as well as Arthur Koestler's and Ken Wilber's description of 'holons' (see 1-2 Nestedness). A living system can be described as a holon, containing its own wholeness; while simultanesouly being nested within a larger system, a larger holon; and all holons are contained within a Universal wholeness.

image by Sergio Cerrato/Pixabay

Structures, components, processes

Carol Sanford reminds designers to begin by perceiving wholeness, especially when planning to intervene in living systems to promote regeneration. While perceiving wholeness, designers can ask more helpful questions about several aspects of living systems. Sanford points out that living systems are self-organizing – they create and arrange their own structures, components, and processes (see 1-7 Networks).

Structures typically support (like a skeleton), circulate (like a river), or contain (like a membrane). Structures can also serve to interlink neighboring systems (like a revolving door, or a ferry).

Components typically organize (concentrate, specialize, or localize) activities. Within the human body, organs are components, often contained by membranes, linked to various activities and sub-systems.

Processes are the ways things typically happen. Several components and structures can be involved in a process. For example, human respiration. Parasympathetic nerve cells stimulate diaphragm muscles, which expand the chest, drawing air into the lungs. Lung cells then absorb oxygen and transfer it to circulating red blood cells, which are then pumped by the heart through blood vessels to deliver oxygen throughout the body.

Some processes have a focus that is more internal, while others are more external. For example: DNA replication and transcription are typically internal processes. Breathing and eating are more external processes, involving interacting with neighboring systems. Membranes are key aspects of these interactions, since they allow for the containment of internal processes, while also remaining open to exchanges with neighboring systems. While living systems are mostly self-reliant, they also typically require a few external inputs, and ways to allow those external inputs to become internalized. They typically develop processes, components, and structures to enable exchanges across membranes (see 3-4 Membranes/Thresholds, see 7-8 Allow Flow).

Sanford argues that it is living systems' wholeness – the combined integration of their structures, components, and processes – that allows regeneration. She further suggests that regeneration necessarily involves these structures, components, and processes. For example: regenerating a degraded forest requires understanding its place within its local context, its watershed and ecosystem; as well as the local economy, and the human needs that likely led to the forest's decline in the first place.

Properties

Daniel Wahl proposes that patterns and properties emerge from the relationships and interactions that arise between the structures, components, and processes of a living system. These patterns and properties contribute to any system's wholeness. Fritjof Capra points out that sustainability can be one of these properties, often involving a whole community and its web of relationships. For designers aiming to improve on sustainability, however, patterns and properties that uplift regeneration may be more helpful.

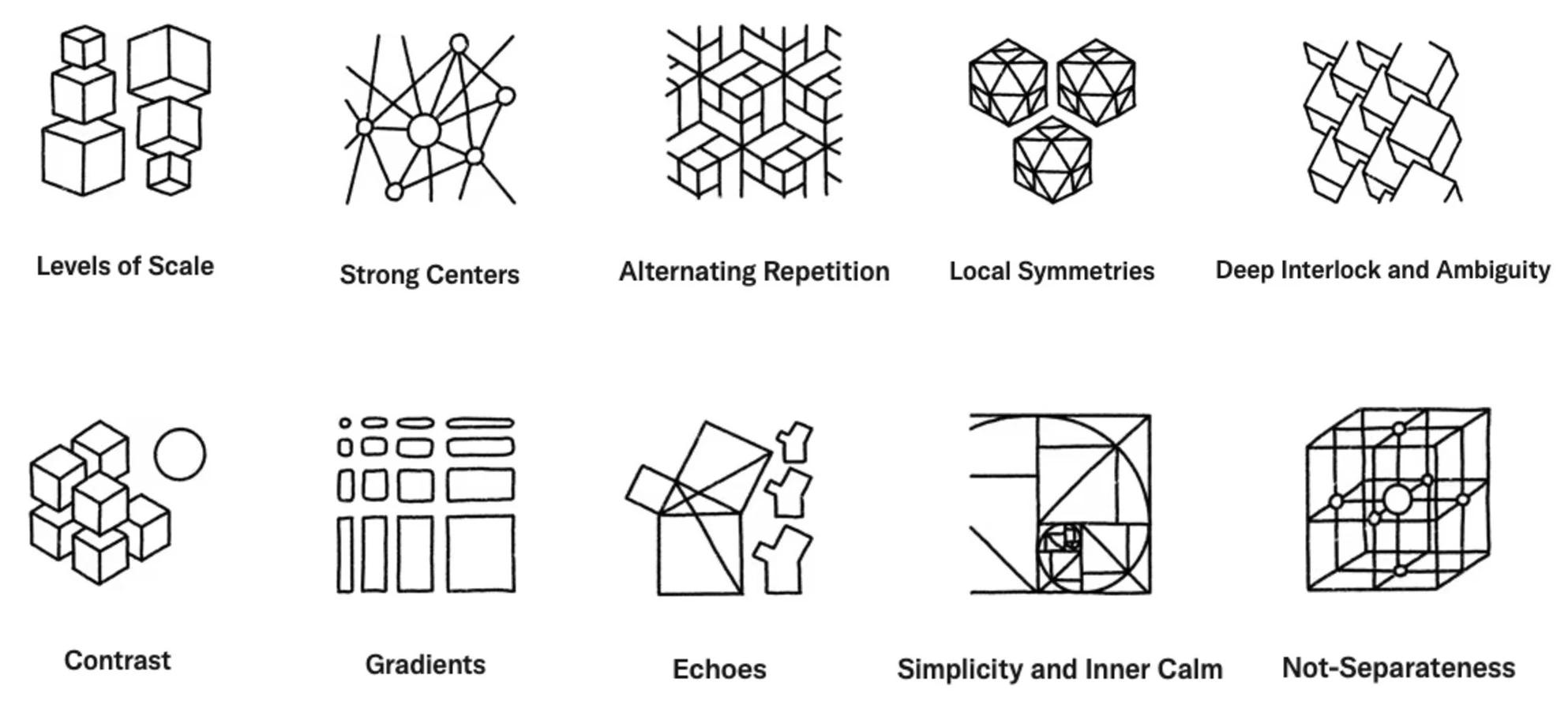

Christopher Alexander attempted to describe such patterns as 'properties of wholeness.' Nikos Salingaros and Dave Hora have continued expanding on Alexander's ideas, exploring how these properties might inform various human designs. They are all based on perceiving wholeness. Some derive from mathematics (Gradients, Local Symmetry, Levels of Scale) or fractal geometry (Altering Repetition, Roughness). Some of these properties are more intuitive and easy to understand (Spacious Boundaries, Contrast, Echoes, Simplicity); others less so (The Void, Good Shapes). Let's explore four of Alexander's properties a little more: Strong Centers; Positive Space; Deep Interlock and Ambiguity; Non-Separateness.

Strong Centers

Dave Hora writes: “In every situation, there is a wholeness that we are working within. From this wholeness – in and of this wholeness – centers arise. The world is constructed from a field of interlocking and overlapping centers. Life comes from the strength, the well-formed-ness, of each center. An amplifying center, or set of centers, helps to bind together the whole. An example: The human head is a center. Each eye, on its own, is a center. The mouth, alone, is a center. The nose, a center. The face – the configuration of eyes, nose, mouth, other features – is a center defined by the centers that contain it, the centers that it contains, and most importantly, the relationships between all of those centers and how they enhance or strengthen each other center in this area of wholeness.” Note the many similarities a 'strong center' shares with a 'holon.'

Positive Space

Dave Hora writes: “In a field of centers exhibiting Positive Space, every bit of space is substantial, it 'swells outward,' it is geometrically and spatially positive. Nothing feels left over. Alexander describes Positive Space where the centers grow together like the kernels of corn on a cob, staying coherent, packing together, adapting themselves each to the adjustment of the other kernels around them.” Nikos Salingaros adds: “Wholes and the spaces between them form an unbroken continuous arrangement.”

diagrams by Camillo Visini

Deep Interlock and Ambiguity

Dave Hora writes: “In living structures centers are “hooked” into their surrounding centers, so centers enmesh in their surroundings. Two centers, seemingly separate, interact with one another or “grip” each other in such a way as to provide clear interlock between their pieces, or ambiguity where their edges come together. In either case, there is some zone between multiple centers where their self-contained-ness breaks down. In successful cases, there is no abruptness, no jarring disconnect. If that zone is particularly well formed and a healthy center in its own right, we may also be looking at a Boundary.” Nikos Salingaros adds: “Forms interpenetrate to link together. Two regions can interpenetrate at a semi-permeable interface, which enables a transition from one region to another. There is ambiguity as to which side of the interface one belongs to while inside the transition region.”

Non-separateness

Dave Hora writes, quoting Alexander: “'Each center is connected to the whole world'. It connects each center, up and down in size, recursively by scaling, to its surroundings, from the smallest detail to the whole world it is a part of.” Nikos Salingaros expands: “Not-separateness comes after achieving coherence. Coherence is an emergent property—not present in the individual components. In a larger coherent whole, no piece can be taken away. Decomposition is neither obvious, nor possible. When every component is cooperating to give a coherent whole, nothing looks separate, and nothing draws attention to itself.”

“This is the goal of adaptive design: a seamless blending of an enormous number of complex components. This is the opposite of willful separateness. Not-separateness goes beyond internal coherence, because the whole connects as much as possible to its environment.” - Nikos Salingaros

Daniel Wahl describes wholeness in living systems as “a set of interconnected elements that together form a coherent pattern.” Again, note the similarity to holons in a coherent holarchy (see 1-2 Nestedness).

More Dynamic, Less Static

Both Daniel Wahl and Carol Sanford emphasize processes, relationships, and interactions. A shift toward perceiving wholeness may involve focusing less on static 'things' and more on dynamic processes.

“A whole is a dynamic 'coming into being' through mutual reciprocity (interbeing) with its parts. Neither the whole nor the parts are primary. They co-arise. The wholeness of nature is not a thing, but a process of 'coming into being' through relationship. So everything is 'natural' and 'nature' manifests through everything... From a participatory understanding of the wholeness of nature, the whole of life is not a thing, but a process that 'comes into being' through all living beings and their relationships. Life is a transformative process that weaves trillions of 'individual' manifestations of being alive through and in relationships into an underlying unity.” – Daniel Wahl

One way to help this shift, to de-emphasize the static and emphasize the dynamic, may be to focus less on nouns and more on verbs. Calvin Po suggests that more-noun-based language can be extractive and disconnective, describing “natural resources” as a bunch of disconnected “inert objects” or “passive backdrops.” More-verb-based language can re-emphasize embodied, active beings and experiences; dynamic connections and patterns of relationship. Perceiving wholeness might reveal how much we humans are entangled with the wider world, mutually participating in a multitude of relationships and their co-arising.

image by Pete Linforth/Pixabay

Emergence: Surprise!

Perceiving wholeness means perceiving more than the sum of the parts. If you view a collection of parts as a bunch of “inert objects,” without any relationships or dynamic interactions between them, you are not perceiving wholeness. The interactions between various components help define “their significance and identity,” their belonging to the wholeness, according to Wahl. It is only through these dynamic interactions that the wholeness “comes into being.” This is a form of mutual dependence: the parts and the whole cannot exist without each other, since they mutually co-arise. (see 1-6 Interdependence). This echoes Salingaros's description of coherence.

The 'something more' that arises, is very difficult to define, predict, or control. Amay Kataria describes it this way: the world is composed of holons at various scales. When holons combine to form holarchies (like a collection of cells combining to form the systems that comprise a human being), 'something more' emerges. A human being is more than a collection of cells and systems.

This property of emergence is intrinsic to wholeness, holons, and every living system. It can express creatively, flexibly, and surprisingly. Arthur Koestler called its unpredictability “something unique and powerful.” Perceiving wholeness may involve noticing what surprises are emerging from the relationships and interactions within and between systems (see 8-8 Allow Emergence, see 4-8 Integrate the Unexpected, see 6-8 Allow Change).

image by Sergio Cerrato/Pixabay

Aliveness, Wellbeing, Healing

Alexander tried to describe this 'something more' in several ways. Speaking most directly to architects, planners, and designers of human spaces, he used terms like 'aliveness.' He asked: how can we humans design and create spaces that feel 'more alive'? He hoped designers would begin to use his properties of wholeness in their designs. He hoped this would add strength, boldness, beauty, and aliveness to human creations, helping them to be more aligned with their surrounding environment, more unified with (or even indistinguishable from) the surrounding wholeness of the world.

Alexander developed his properties of wholeness between the 1950s and 1980s, when plenty of 'modernists' were designing and creating sterile spaces devoid of aliveness, disconnected from a sense of wholeness. Some of the built environments of this time (inside which many people still live today) are deliberately 'incoherent', lacking the properties of wholeness. They were designed to be disturbing, alarming, and exciting, drawing attention to their architects. Salingaros states that such violation of the properties of wholeness “causes physiological anxiety for the users.” He claims that such 'brutalism' affects people subconsciously, and may reinforce a sense of dis-ease and lack of wellbeing.

Salingaros proposes instead studying the properties of wholeness, which give rise to coherent forms. He says that “coherence is healing:” it promotes wellbeing. Alexander also used the term 'healthy.' The words 'whole,' 'health,' and 'healing' all come from the same root stem. To heal literally means 'to make whole.' Or to re-connect to a surrounding wholeness. Alexander advocated for creating healthy structures in human built environments – buildings designed with the properties of wholenes, that promote aliveness, health, and wellbeing.

Salingaros further suggests that “making wholeness heals the maker." When you design with wholeness in mind, you yourself become 'healed;' you become more whole in your own self, and you become part of that wholeness you help to create. Wholeness therefore has bearing on your own well-being. This is why, on a deep level, you feel 'more alive' in a whole and healthy environment. Hora puts it like this: you feel 'more alive' when you interact with environments that feel 'more alive.' Such spaces help you to feel more connected to the surrounding wholeness, and thus to become more whole.

Hora notes how expansively Alexander's ideas could be applied: many societal institutions could be re-designed with wholeness in mind. Any aspect of human creation – from the built environment to activities, organizations, policies, or laws – could be re-designed to feel 'more alive,' to contribute to wellbeing and wholeness (see 4-1 Health, see 4-4 Collective Responsibility).

Designing with Wholeness in Mind

Expand the individual view. Donella Meadows contradicts the popular notion held by capitalist economists that systems are best guided by individual self-interest. She argues that the individual view is not the best basis for determining the wellbeing of a whole system. “The bounded rationality of each actor in a system may not lead to decisions that further the welfare of the system as a whole.” Expanding the individual view by perceiving wholeness may be more helpful (see 4-4 Collective Responsibility).

Beware the analysis of parts. Fritjof Capra reminds designers that deconstructing and analyzing the parts of a system rarely aids in understanding a system's wholeness. Even the properties of parts “can only be understood within the context of the larger whole.” Carol Sanford agrees that parts analysis, while common, is ultimately unhelpful, a pathway away from perceiving wholeness.

Beware over-focus on function. A capitalist-individualist worldview (which is very common in westernized societies) typically over-focuses on function, asking 'what does it do?', 'what is it for?', 'what can it do for me?' or 'what can I get out of it?' Carol Sanford cautions that such an approach tends to fragment wholeness, and ends up emphasizing parts again, not perceiving wholeness.

Use frameworks, not models. Meadows reminds designers that “everything we think we know about the world is a model. While models do have strong congruence with reality, they fall short of representing the real world fully.” Sanford warns against over-reliance upon models, since in westernized societies they typically represent a predict-and-control cookie-cutter approach to replicating something precisely. Models are often used to design factory assembly-lines, to conform to a pre-existing patttern, or to problem-solve by generating answers. By contrast, frameworks help generate questions, says Sanford. This allows designers to “repeatedly rethink a situation or project, inviting higher quality reasoning, intuition and energy, as it reveals evolving connections and relationships.” A framework can help generate new questions and thinking that are more relevant to changing contexts, timings, and patterns. Compared to models, frameworks are a much better tool for perceiving wholeness.

image by DGSstudios/Pixabay

Use systems thinking. Fritjof Capra calls systems thinking “seeing interrelationships rather than things; seeing patterns of change rather than static 'snapshots.'” Charles Krone advised “using systemic frameworks and developmental processes to consciously improve the capacity to apply systems thinking to the evolution of human or social living systems.”

Promote regenerative development. Pamela Mang and Bill Reed suggest designers “develop strategic systemic thinking capacities... to ensure regenerative design processes achieve maximum systemic leverage and support.” They suggest designers find “technologies and strategies for generating the patterned whole-system understanding of a place.” They define “place” as: “the unique, multilayered network of ecosystems within a geographic region that results from the complex interactions through time of the natural ecology (climate, mineral deposits, soil, vegetation, water, wildlife) and culture (distinctive customs, expressions of values, economic activities, forms of association, ideas for education, traditions).”

Healing and Regenerating

Quoting several dictionaries, Mang and Reed offer this definition: “Regenerate: To give new life or energy; to revitalize; to bring or come into renewed existence; to impart more vigorous life. To form, construct, or create anew, especially in an improved state; to restore to a better state, refreshed or renewed. To improve a place or system, especially by making it more active or successful.” To this they add Jenkin and Pedersen Zari's definition of “restorative design: a design system that combines returning 'polluted, degraded or damaged sites back to a state of acceptable health through human intervention' with biophiliac designs that reconnect people to nature.”

As regenerative designers, we have a responsibility to “prioritize the good of the whole system,” as Donella Meadows put it. As we shift toward perceiving wholeness, we can better uplift systems thinking, re-framing problems, and generating questions that better address everyone's needs. We can imagine regenerative and restorative designs, ones that will leave the world better than how we found it.

Dave Hora says that the world is not always beautiful or comfortable, nor are human creations always sensibly designed. These can be improved, and as designers, we can be the ones to begin improving them. “Where we have influence on the structure of some area of the world, we can and should work to heal that place.” To work to heal a place is to strive to make it more whole, or more connected to its surrounding wholeness. Carol Sanford urges us to begin by perceiving wholeness, then to work regeneratively to increase wholeness and healing.

“Those who work with wholes create cascades of beneficial change through strategic interventions. This is the way we need to work, by intervening intelligently in whole systems for the purpose of regenerating them.” – Carol Sanford

image by Okan Kaliskan/Pixabay

References

Alexander, Christopher; S. Ishikawa; M. Silverstein; M. Jacobson; I. Fiksdahl-King; S. Angel (1977). A Pattern Language. Oxford University Press.

Alexander, Christopher (2002). The Nature of Order, Book 1: The Phenomenon of Life. Routledge.

Alexander, Christopher (2002). The Nature of Order, Book 2: The Process of Creating of Life. Routledge.

Alexander, Christopher (2002). The Nature of Order, Book 3: A Vision of a Living World. Routledge.

Alexander, Christopher (2003). The Nature of Order, Book 4: The Luminous Ground. Routledge.

Capra, Fritjof (1996). The Web of Life: a new scientific understanding of living systems. Anchor Books.

Capra, Fritjof and Pier Luigi Luisi (2014). The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision. Cambridge University Press.

DeKay, Mark (2011). Integral Sustainable Design: Transformative Perspectives. Earthscan. DOI:10.4324/9781849775366

Hora, Dave (2020). “Nature of Order #1: Christopher Alexander's work and its importance in shaping a healthy, living world.”

Hora, Dave (2020). “Nature of Order #2: The First Eight of Christopher Alexander's 15 Fundamental Properties of Wholeness.”

Hora, Dave (2020). “Nature of Order #3: Nos. 9-15 of Christopher Alexander's 15 Fundamental Properties of Wholeness.”

Jenkin S, and M. Pedersen Zari (2009). “Rethinking Our Built Environments: towards a sustainable future.” Ministry for the Environment, Manatu Mo Te Taiao, Wellington.

Kataria, Amay (2020). “A Brief Primer on Holons and Holarchy.” https://www.manacontemporary.com/editorial/a-brief-primer-on-holons-and-holarchy/

Koestler, Arthur (1967). The Ghost in the Machine. Hutchinson.

Krone, Charles (2001). West coast resource development: session notes. Unpublished transcription of dialogue by members of the Institute for Developmental Processes, Carmel

Mang, Pamela and Bill Reed (2012). “Regenerative Development and Design.” In: Meyers, R.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0851-3_303

Meadows, Donella (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green.

Po, Calvin (2023). "Verbs Not Nouns: How language can shape alternate worldviews." https://nowthenmagazine.com/articles/verbs-not-nouns-how-language-can-shape-alternate-worldviews-giyu-tjauvaljian-yu-chieh-wu

Roös, Phillip B. (2021). "Living Structures: The Fundamental Properties of Wholeness" in: Regenerative-Adaptive Design for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53234-5_9

Salingaros, Nikos Angelos (2013). "ch. 11 (19). Christopher Alexander's 15 Fundamental Properties." In Unified Architectural Theory: Form, Language, Complexity—a Companion to Christopher Alexander's "The Phenomenon of Life : the Nature of Order, Book 1", 125-130. Sustasis Foundation and Vajra Books. https://patterns.architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-172521

Salingaros, Nikos Angelos (2012). "“Making Wholeness Heals the Maker”: Why Human Flourishing Requires the Creative Act." Crisis Magazine.

Sanford, Carol (2016). "Living Structured Wholes." https://sustainablebrands.com/read/organizational-change/regenerative-business-part-2-discerning-a-living-structured-whole-and-avoiding-part-thinking

Wahl, Daniel (2016). Designing Regenerative Cultures. Triarchy Press.

Wilber, Ken (1995). Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution. Shambhala.

Root Cuthbertson

loves dancing, music, poetry, public libraries, matching needs with resources, monofloral honeys, generously inclusive humor, and stories about healing and hope. He has studied social change movements, comparative religion, needs-based approaches, de-colonization, and liberation for all. He holds a Master’s Degree in Environmental Education, and certificates in Sustainable Curriculum Design, Participatory Facilitation, and Ecopsychology. A certified trainer in Gaia Education eco-social design, Root designs experiential opportunities for learning by creating strong containers for the graceful facilitation of group energy. With his wife Deborah Benham, he has delivered trainings on Sociocracy, Culture Repair, and the Connection 1st online courses: “Introduction to Regenerative Community Building,” “Designing for Peace,” and "Pathways to Village Building.” Former Training Coordinator for Transition Network, he is the co-author and curator of collections on Personal Resilience, Conflict Resilience, Group Culture, and Social Justice. With Jon Young and Deborah, he is co-authoring a series of e-books on regenerative community design. With his ear to the ground, Root’s guiding question is: “What is most needed here now?”

![]()